What Is a Cycle That Tends to Repeat Over Again

Mark Twain: "a favorite theory of mine [is] that no occurrence is sole and solitary, merely is but a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and perhaps often."[1]

Celebrated recurrence is the repetition of similar events in history.[a] [b] The concept of historic recurrence has variously been applied to the overall history of the globe (eastward.one thousand., to the rises and falls of empires), to repetitive patterns in the history of a given polity, and to whatever two specific events which bear a striking similarity.[4]

Hypothetically, in the extreme, the concept of historic recurrence assumes the form of the Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence, which has been written nearly in various forms since antiquity and was described in the 19th century by Heinrich Heine[c] and Friedrich Nietzsche.[d]

While it is oft remarked that "history repeats itself", in cycles of less than cosmological duration this cannot be strictly true.[e] In this interpretation of recurrence, as opposed perhaps to the Nietzschean interpretation, there is no metaphysics. Recurrences take identify due to ascertainable circumstances and chains of causality.[f] An example is the ubiquitous miracle of multiple contained discovery in science and technology, described by Robert K. Merton and Harriet Zuckerman. Indeed, recurrences, in the form of reproducible findings obtained through experiment or observation, are essential to the natural and social sciences; and, in the course of gamble observations rigorously studied via the comparative method, are essential to the humanities.

One thousand.W. Trompf, in his book The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, traces historically recurring patterns of political thought and behavior in the west since artifact.[10] If history has lessons to impart, they are to be establish par excellence in such recurring patterns.

Historic recurrences of the "striking-similarity" type tin can sometimes induce a sense of "convergence", "resonance" or déjà vu.[k]

[edit]

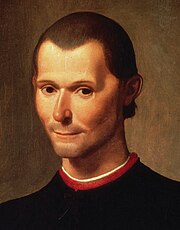

Aboriginal western thinkers who had thought near recurrence had largely been concerned with cosmological rather than celebrated recurrence (run across "eternal render", or "eternal recurrence").[11] Western philosophers and historians who have discussed various concepts of celebrated recurrence include the Greek Hellenistic historian Polybius (ca 200 – ca 118 BCE), the Greek historian and rhetorician Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. threescore BCE – subsequently 7 BCE), Luke the Evangelist, Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), Giambattista Vico (1668–1744), Arnold J. Toynbee (1889–1975).[iv]

An eastern concept that bears a kinship to western concepts of celebrated recurrence is the Chinese concept of the Mandate of Heaven, by which an unjust ruler will lose the support of Heaven and exist overthrown.[12]

G.West. Trompf describes various historic paradigms of historic recurrence, including paradigms that view types of large-calibration historic phenomena variously as "cyclical"; "fluctuant"; "reciprocal"; "re-enacted"; or "revived".[13] He likewise notes "[t]he view proceeding from a conventionalities in the uniformity of human nature [Trompf'south emphasis]. It holds that considering human nature does not change, the same sort of events can recur at any time."[14] "Other pocket-sized cases of recurrence thinking," he writes, "include the isolation of whatever two specific events which bear a very hit similarity [his emphasis], and the preoccupation with parallelism [his emphasis], that is, with resemblances, both general and precise, between dissever sets of historical phenomena."[xiv]

Lessons [edit]

G.Westward. Trompf notes that nearly western concepts of historic recurrence imply that "the past teaches lessons for... future action"—that "the aforementioned... sorts of events which have happened before... volition recur..."[15] One such recurring theme was early offered by Poseidonius (a Greek polymath, native to Apamea, Syria; ca 135–51 BCE), who argued that dissipation of the old Roman virtues had followed the removal of the Carthaginian challenge to Rome's supremacy in the Mediterranean world.[16] The theme that civilizations flourish or fail co-ordinate to their responses to the homo and environmental challenges that they face, would be picked upward 2 thousand years later past Toynbee.[17] Dionysius of Halicarnassus (c. 60 BCE – later on vii BCE), while praising Rome at the expense of her predecessors[h]—Assyria, Media, Persia, and Republic of macedonia—anticipated Rome's eventual decay. He thus implied the idea of recurring decay in the history of globe empires—an idea that was to exist adult by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE) and by Pompeius Trogus, a 1st-century BCE Roman historian from a Celtic tribe in Gallia Narbonensis.[xix]

By the late 5th century, Zosimus (also called "Zosimus the Historian"; fl. 490s–510s: a Byzantine historian who lived in Constantinople) could encounter the writing on the Roman wall, and asserted that empires fell due to internal disunity. He gave examples from the histories of Greece and Macedonia. In the case of each empire, growth had resulted from consolidation against an external enemy; Rome herself, in response to Hannibal'due south threat posed at Cannae, had risen to great-power condition within a mere five decades. With Rome's world dominion, yet, aristocracy had been supplanted past a monarchy, which in plow tended to disuse into tyranny; after Augustus Caesar, good rulers had alternated with tyrannical ones. The Roman Empire, in its western and eastern sectors, had become a contending ground between contestants for power, while outside powers acquired an advantage. In Rome's disuse, Zosimus saw history repeating itself in its general movements.[20]

The ancients developed an indelible metaphor for a polity's evolution, cartoon an analogy betwixt an private human'southward life cycle and developments undergone past a body politic: this metaphor was offered, in varying iterations, by Cicero (106–43 BCE), Seneca (c. 1 BCE – 65 CE), Florus (c. 74 CE – ca 130 CE), and Ammianus Marcellinus (betwixt 325 and 330 CE – after 391 CE).[21] This social-organism metaphor, which has been traced dorsum to the Greek philosopher and polymath Aristotle (384–322 BCE),[22] would recur centuries afterwards in the works of the French philosopher and sociologist Auguste Comte (1798–1857), the English philosopher and polymath Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), and the French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917).[23]

Niccolò Machiavelli, analyzing the country of Florentine and Italian politics between 1434 and 1494, described recurrent oscillations betwixt "order" and "disorder" inside states:[24]

when states accept arrived at their greatest perfection, they shortly begin to decline. In the same manner, having been reduced past disorder and sunk to their utmost state of low, unable to descend lower, they, of necessity, reascend, and thus from good they gradually pass up to evil and from evil mount upwards to good.[25]

Machiavelli accounts for this oscillation by arguing that virtù (valor and political effectiveness) produces peace, peace brings idleness (ozio), idleness disorder, and disorder rovina (ruin). In turn, from rovina springs society, from club virtù, and from this, glory and good fortune.[26] Machiavelli, every bit had the ancient Greek historian Thucydides, saw human nature as remarkably stable—steady enough for the conception of rules of political beliefs. Machiavelli wrote in his Discorsi:

Whoever considers the past and the nowadays volition readily observe that all cities and all peoples... ever have been animated by the same desires and the same passions; and then that it is easy, by diligent study of the past, to foresee what is likely to happen in the future in any republic, and to apply those remedies that were used by the ancients, or not finding whatever that were employed by them, to devise new ones from the similarity of events.[27]

In 1377 the Islamic scholar Ibn Khaldun, in his Muqaddima (or Prolegomena), wrote that when nomadic tribes become united by asabiyya—Arabic for "group feeling", "social solidarity", or "clannism"—their superior cohesion and military prowess puts urban dwellers at their mercy. Inspired often past religion, they conquer the towns and create new regimes. But within a few generations, writes Ibn Khaldun, the victorious tribesmen lose their asabiyya and get corrupted by luxury, extravagance, and leisure. The ruler, who can no longer rely on vehement warriors for his defence, will have to heighten extortionate taxes to pay for other sorts of soldiers, and this in turn may lead to further problems that effect in the eventual downfall of his dynasty or state.[28] [i]

Joshua South Goldstein suggests that empires, analogously to an individual's midlife crisis, experience a political midlife crisis: subsequently a menstruation of expansion in which all earlier goals are realized, overconfidence sets in, and governments are then probable to attack or threaten their strongest rival; Goldstein cites four examples: the British Empire and the Crimean War; the German language Empire and the First World War; the Soviet Wedlock and the Cuban Missile Crisis; the U.s.a. and the Vietnam War.[xxx] Suggestions that the European Union is suffering a political midlife crunch have been put forward by Gideon Rachman (2010), Roland Benedikter (2014), and Natalie Nougayrède (2017).

David Hackett Fischer has identified four waves in European history, each of some 150-200 years' duration. Each wave begins with prosperity, leading to inflation, inequality, rebellion and war, and resolving in a long menstruum of equilibrium. For example, 18th-century inflation led to the Napoleonic wars and after the Victorian equilibrium.[31]

Sir Arthur Keith'south theory of a species-broad amity-enmity complex suggests that human censor evolved every bit a duality: people are driven to protect members of their in-grouping, and to hate and fight enemies who belong to an out-group. Thus an endless, useless bicycle of advert hoc "isms" arises.[32]

Similarities [edit]

One of the recurrence patterns identified by G.W. Trompf involves "the isolation of any ii specific events which behave a very hit similarity".[xv] The Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana observed that "Those who cannot retrieve the past are condemned to repeat information technology."[33] Karl Marx, having in mind the corresponding coups d'état of Napoleon I (1799) and his nephew Napoleon Three (1851), wrote acerbically in 1852: "Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the start fourth dimension as tragedy, the 2d time as farce."[34]

Yet, Poland'due south Adam Michnik believes that history is not merely about the by because information technology is constantly recurring, and not as farce, as Marx had it, but every bit itself: "The earth", writes Michnik, "is full of inquisitors and heretics, liars and those lied to, terrorists and the terrorized. There is still someone dying at Thermopylae, someone drinking a glass of hemlock, someone crossing the Rubicon, someone cartoon upwards a proscription listing."[35]

Plutarch's Parallel Lives traces the similarities between pairs of a Roman and a Greek historical figure.[36]

Poland'due south Catholic Primate, Stanisław Szczepanowski, is murdered past his one-time friend, Male monarch Bolesław the Bold (1079); and England's Catholic Primate, Thomas Becket, is murdered at the bidding of his onetime friend, Male monarch Henry 2 (1170).

Mongolian Emperor Kublai Khan'southward attempted conquest of Japan (1274, 1281) is frustrated by typhoons;[j] and Spanish King Philip Two's 1588 attempted conquest of England is frustrated by a hurricane.

Hernán Cortes'south fateful 1519 entry into Mexico's Aztec Empire is reputedly facilitated by the natives' identification of him with their god Quetzalcoatl, who had been predicted to render that very year; and English language Captain James Cook's fateful 1778 entry into Hawaii, during the almanac Makahiki festival honoring the fertility and peace god Lono, is reputedly facilitated by the natives' identification of Cook with Lono,[37] who had left Hawaii, promising to return on a floating isle, evoked by Melt'due south ship under full sail.[38]

On 27 Apr 1521, Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, in the Philippine Islands, foolhardily, with only iv dozen men, confronts 1,500 natives who take defied his try to Christianize them and is killed.[39] On xiv Feb 1779, English language explorer James Cook, on Hawaii Island, foolhardily, with only a few men, confronts the natives later some individuals accept taken 1 of Melt'due south small boats, and Cook and four of his men are killed.[40]

Poland's Queen Jadwiga, dying in 1399, bequeaths her personal jewelry for the restoration of Kraków University (which will occur in 1400); and Leland Stanford'south widow Jane Stanford attempts, later on his 1893 decease, to sell her personal jewelry to restore Stanford University's fiscal viability, ultimately bequeathing the jewelry to fund the purchase of books for Stanford Academy.[k]

In 1812 French Emperor Napoleon – born a Corsican outsider – is unprepared for an extended winter campaign, yet invades the Russian Empire, precipitating the autumn of the French Empire; and in 1941 German Führer Adolf Hitler – born an Austrian outsider – is unprepared for an extended winter campaign, yet invades the Russian Empire's Soviet successor state (which is ruled by Joseph Stalin, born a Georgian outsider), thus precipitating the fall of the German Third Reich.[41]

Mahatma Gandhi works to liberate his compatriots by peaceful means and is shot dead; Martin Luther King Jr., works to liberate his compatriots by peaceful means and is shot dead.[42]

Over history, confrontations betwixt peoples – typically, geographical neighbors – help consolidate the peoples into nations, at times into frank empires; until at final, exhausted past conflicts and drained of resource, the once militant polities settle into a relatively peaceful habitus.[43] [fifty]

Polities ignore Jan Bloch's 1898 warnings of the railroad-mobilized, industrialized, stalemated, attritional total war, World War I, that is on the manner and will destroy an appreciable office of flesh;[45] and polities ignore geologists', oceanographers', atmospheric scientists', biologists', and climatologists' warnings of the climate-change tipping point that is on course to destroy all of mankind.[46] [one thousand]

People ignore warnings about the dangers of nuclear power plants[48] until anticipated nuclear power-plant accidents occur; and people ignore warnings about the dangers of nuclear weapons[49] [n] [51] until some city in the world is diddled up by a nuclear weapon.

Jessica Tuchman Mathews, girl of The Guns of August author Barbara Tuchman, observes that "[P]owerful reasons to dubiety that there could be a express nuclear war [include] those that emerge from whatsoever written report of history, a knowledge of how humans act nether pressure, or experience of government."[52] Apposite evidence for this is provided in Martin J. Sherwin's Gambling with Armageddon, which makes clear, on the ground of recently declassified documents, that it was a thing of sheer run a risk that war was averted during the Cuban Missile Crunch: numerous events, had they taken a slightly different form, could each have precipitated nuclear state of war.[53] [o]

Fintan O'Toole writes nearly American war correspondent Martha Gellhorn (1908–98):

Her dispatches were not first drafts of history; they were letters from eternity. [...] To meet history – at to the lowest degree the history of war – in terms of people is to run into information technology not as a linear process merely as a series of terrible repetitions [...]. It is her ability to capture [...] the terrible futility of this sameness that makes Gellhorn's reportage and so genuinely timeless. [Westward]e are [...] drawn [...] into the undertow of her distraught sensation that this moment, in its essence, has happened before and volition happen once more.[55]

Casey Cep, describing a dissonance between William Faulkner'south documented personal racism and Faulkner's depiction of the American Confederacy, writes that Michael Gorra, in The Saddest Words: William Faulkner's Ceremonious War ([Liveright, 2020),

posits that [the character] Quentin [Compson, who suicides in Absalom, Absalom!] represents Faulkner's view of tragedy as recurrence. "Once more" was the saddest give-and-take for the graphic symbol and the writer alike considering it "suggests that what was has but gone on happening, a cycle of repetition that replays itself, forever."... "What was is never over," Gorra writes, pointing out that the racism that ensnared Faulkner in the last century persists in thursday[east 21st]... "Again. That'south precisely why Faulkner remains and then valuable – that very recurrence makes him necessary."[56]

British novelist Martin Amis observes that recurring patterns of imperial ascendance-and-decline are mirrored in the novels published; co-ordinate to Amis, novels follow electric current political trends. In the Victorian era, when Britain was the ascendant power, British novels were large and tried to express what society as a whole was. British power waned during the Second World State of war and ended afterward the war. The British novel was and so some 225 pages long and centered on narrower subjects such as career setbacks or marriage setbacks: the British novel's "great tradition" increasingly looked depleted. Ascendance, according to Amis, had passed to the United states of america, and Americans such every bit Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, and John Updike began writing huge novels.[57]

Novelists and historians have discerned recurrent patterns in the histories of modern political tyrants.[58]

Gabriel García Márquez, in his novelThe Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), [...] create[d] a composite character: a mythical, unnamed autocrat who has held sway, seemingly forever, over an invented Caribbean area country akin to Costaguana in Joseph Conrad'due south Nostromo. To portray him, García Márquez drew upon a motley cohort of Latin American caudillos [...] besides as Espana'south Generalissimo Francisco Franco [...].[59]

Ruth Ben-Ghiat in Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present (2020), writes Ariel Dorfman, documents the "viral recurrence" around the world, over the past century, of despots and authoritarians "with comparable strategies of control and mendacity." Ben-Ghiat divides the narrative into three – at times, overlapping – periods:[threescore]

The era of fascist takeovers runs from 1919 and the ascension of Mussolini until Hitler'south defeat in 1945, with Franco as the third fellow member of this awful trio [... In] the next phase, the historic period of armed services coups (1950–1990) [t]he main representatives [...] are Pinochet, Muammar Qaddafi, and Mobutu Sese Seko, along with minor figures like Idi Amin, Saddam Hussein, and Mohamed Siad Barre. Finally, starting in 1990 [is] the [...] cycle of new authoritarians, who win elections and proceed to degrade the republic that brought them to power. Ben-Ghiat primarily dissects Silvio Berlusconi, Vladimir Putin, and Donald Trump, with Viktor Orbán, Jair Bolsonaro, Rodrigo Duterte, Narendra Modi, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan given perfunctory assessments.[61]

Dorfman notes the absence, from Ben-Ghiat's study, of many authoritarian rulers, including communists like Mao, Stalin, Ceaușescu, and the iii Kims of North korea. Nor is there mention of Indonesia'south Suharto or the Shah of Islamic republic of iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, "though the CIA engineered coups that led to both [...] lording information technology over their lands, and the agency can also be linked to Pinochet's armed services putsch in Chile." Dorfman believes that Juan Domingo Perón would also have been an instructive case to include in Ruth Ben-Ghiat's study of Strongmen.[62]

British political commentator Ferdinand Mountain brings attention to the ubiquitous recurrence of mendacity in politics: politicians lie to comprehend upward their mistakes, to gain advantage over their opponents, or to achieve purposes that might exist unpalatable or harmful to their public or to a strange public. Some notable practitioners of political mendacity discussed by Mount include Julius Caesar, Cesare Borgia, Queen Elizabeth I, Oliver Cromwell, Robert Clive, Napoleon, Winston Churchill, Tony Blair, Boris Johnson, and Donald Trump,[63]

Run into likewise [edit]

- Amity-enmity complex

- The Beefcake of Revolution

- Large Bang

- Big Bounciness (pulsating-universe theory)

- Cliodynamics

- Dark (TV series)

- Eternal render

- Exceptionalism

- Eureka: A Prose Verse form, by Edgar Allan Poe, 1848 (Big Bang theory)

- Fractal

- Generation Zero

- Is the Holocaust Unique?

- Lest We Forget

- List of multiple discoveries

- List of pre-modern cracking powers

- Multiple discovery

- Never again

- Peter Turchin

- Philosophy of history

- Political midlife crisis

- Repetition, a related concept past Søren Kierkegaard

- The Rise and Autumn of the Smashing Powers

- Societal collapse

- Land collapse

- Strauss-Howe generational theory

- The Truthful Believer

- Thucydides Trap

Notes [edit]

- ^ Mark Twain writes of "a favorite theory of mine—to wit, that no occurrence [Twain'south emphasis] is sole and solitary, but is merely a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and possibly often." (A "echo occurrence" is the definition of "recurrence".)[1] A like thought of uncertain attribution has been ascribed to Twain: "History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes."[two]

- ^ Herman Melville, in his poetry, "declare[d a] belief... that all history is mere iteration ('Age after age shall be/As age subsequently age has been')..."[3]

- ^ Philosopher Walter Kaufmann quotes Heinrich Heine: "[T]ime is infinite, but the things in time, the physical bodies, are finite. They may indeed disperse into the smallest particles; but these particles, the atoms, accept their determinate numbers, and the numbers of the configurations which, all of themselves, are formed out of them are likewise determinate. Now, all the same long a fourth dimension may pass, according to the eternal laws governing the combinations of this eternal play of repetition, all configurations which have previously existed on this earth must yet see, concenter, repulse, osculation, and corrupt each other again..."[5]

- ^ The concept of "eternal recurrence" is fundamental to the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. It appears in The Gay Scientific discipline and in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and also in a posthumous fragment. Walter Kaufmann suggests that Nietzsche may have encountered the concept in the writings of Heinrich Heine.[6]

- ^ G.Due west. Trompf writes: "The thought of exact recurrence... was rarely incorporated into... these views, for in the main they only presume the recurrence of sorts of events, or... event-types, -complexes, and -patterns."[7]

- ^ In 1814 Pierre-Simon Laplace published an early articulation of causal or scientific determinism: "We may regard the present country of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that prepare nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is equanimous, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to assay, information technology would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect, nada would be uncertain and the future, just like the past, would be present before its eyes."[viii] A similar view had earlier been presented in 1763 by Roger Boscovich.[nine]

- ^ This sense is somewhat suggested, in pop culture, past the picture show Groundhog Day.

- ^ His was thus a quasi-exceptionalist view.[xviii]

- ^ Toynbee regarded Ibn Khaldun'southward Muqaddima as "undoubtedly the greatest work of its kind that has ever been created by whatsoever listen in any time or place."[29]

- ^ The original kamikaze ("divine wind").

- ^ The Stanford University Museum of Art displays a painting of Jane Stanford's jewelry, commissioned prior to the jewelry'due south anticipated sale.

- ^ Victor Bulmer-Thomas writes: "Imperial retreat is not the same equally national decline, as many other countries can attest. Indeed, imperial retreat can strengthen the nation-country just every bit majestic expansion can weaken it."[44]

- ^ On 8 October 2018 the Intergovernmental Console on Climate Alter published a report stating that, if drastic changes in the global free energy base of operations and lifestyle are not made past about 2030—within a dozen years—culture on planet World volition become unsalvageable.[47]

- ^ Nuclear weapons keep to be equally chancy to their owners every bit to their potential targets. Nether the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, nuclear-weapon states are supposed to piece of work toward the elimination of nuclear weapons from the world.[50]

- ^ One of the many factors that fortuitously combined to avert Armageddon was President Kennedy's earlier experience involving Cuba: according to Ted Sorensen, after the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs invasion "he was more skeptical of the recommendations which came to him from the experts," most of whom now brash invading or bombing Cuba.[54]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Mark Twain, The Jumping Frog: In English, Then in French, and And then Clawed Back into a Civilized Language Once more by Patient, Unremunerated Toil, illustrated past F. Strothman, New York and London, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1903, p. 64.

- ^ "History Does Non Repeat Itself, But It Rhymes". Quote Investigator. January 12, 2014.

- ^ Helen Vendler, "'No Poesy You Have Read'" (review of Hershel Parker, ed., Herman Melville: Complete Poems, Library of America, 990 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 19 (5 December 2019), pp. 29, 32–34. (Quotation from p. 32.)

- ^ a b Thousand.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, passim.

- ^ Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, 1959, p. 276.

- ^ Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, 1959, p. 276.

- ^ G.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 3.

- ^ Pierre-Simon Laplace, A Philosophical Essay, New York, 1902, p. iv.

- ^ Carlo Cercignani, chapter ii: "Physics before Boltzmann", in Ludwig Boltzmann: The Man Who Trusted Atoms, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-850154-4, p. 55.

- ^ G.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Idea, passim.

- ^ Thou.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, pp. six-15.

- ^ Elizabeth Perry, Challenging the Mandate of Heaven: Social Protest and State Power in Prc, Sharpe, 2002, ISBN 0-7656-0444-two, passim.

- ^ Thousand.West. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, pp. 2-three and passim.

- ^ a b Thousand.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Idea, p. three and passim.

- ^ a b Chiliad.W. Trompf, The Thought of Historical Recurrence in Western Idea, p. 3.

- ^ G.West. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 185.

- ^ Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History, 12 volumes, Oxford Academy Press, 1934–61, passim.

- ^ K.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 192.

- ^ Thou.W. Trompf, The Thought of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, pp. 186–87.

- ^ K.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, pp. 187–88.

- ^ G.West. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, pp. 188–92.

- ^ George R. MacLay, The Social Organism: A Short History of the Idea that a Human being Society May Be Regarded equally a Gigantic Living Animate being, N River Printing, 1990, ISBN 0-88427-078-5, passim.

- ^ George R. MacLay, The Social Organism: A Brusque History of the Thought that a Human Gild May Be Regarded as a Gigantic Living Animate being, N River Press, 1990, ISBN 0-88427-078-5, passim.

- ^ G.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 256.

- ^ G.Westward. Trompf, The Thought of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 256.

- ^ G.Westward. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 256.

- ^ G.W. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, p. 258.

- ^ Malise Ruthven, "The Otherworldliness of Ibn Khaldun" (review of Robert Irwin, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 9780691174662, 243 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 2 (February 7, 2019), p. 23.

- ^ Malise Ruthven, "The Otherworldliness of Ibn Khaldun" (review of Robert Irwin, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 9780691174662, 243 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 2 (February vii, 2019), p. 23.

- ^ Joshua South Goldstein, Long Cycles: Prosperity and War in the Modern Age, 1988, passim.

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, The Peachy Moving ridge: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History, Oxford University Press, 1996, passim.

- ^ Arthur Keith, A New Theory of Human Development, Watts, 1948, passim.

- ^ George Santayana, The Life of Reason, vol. 1: Reason in Common Sense, 1905.

- ^ The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), in Marx Engels Selected Works, volume I, p. 398.

- ^ Paul Wilson, "Adam Michnik: A Hero of Our Time," The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. six (April 2, 2015), p. 74.

- ^ James Romm, ed., Plutarch: Lives that Made Greek History, Hackett Publishing, 2012, p. half dozen.

- ^ Jenny Uglow, "Isle Hopping" (review of Captain James Cook: The Journals, selected and edited past Philip Edwards, London, Folio Society, three volumes and a chart of the voyages, 1,309 pp.; and William Frame with Laura Walker, James Cook: The Voyages, McGill-Queen University Press, 224 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 2 (February seven, 2019), p. nineteen (total review: pp. 18-20).

- ^ Ross Cordy, Exalted Sits the Chief: The Aboriginal History of Hawai'i Island, Mutual Publishing, 2000, p. 61.

- ^ "The Death of Magellan, 1521". Eyewitnesstohistory.com. Retrieved xvi November 2010.

- ^ Collingridge, Vanessa (2003). Helm Cook: The Life, Decease and Legacy of History's Greatest Explorer. Ebury Printing. ISBN978-0-09-188898-5. , p. 410.

- ^ Englund, Steven (March 2006). "Napoleon and Hitler". Journal of The Historical Society. 6 (1): 151–169. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2006.00171.x.

- ^ Morselli, Davide; Passini, Stefano (2010). "Fugitive crimes of obedience: A comparative written report of the autobiographies of M. G. Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King, Jr". Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. sixteen (three): 295–319. doi:x.1080/10781911003773530. ISSN 1532-7949.

- ^ Paul Kennedy, The Ascent and Fall of the Keen Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000, New York, Random House, 1987, ISBN 0-394-54674-1, passim.

- ^ Jackson Lears, "Purple Exceptionalism" (review of Victor Bulmer-Thomas, Empire in Retreat: The Past, Present, and Futurity of the United States, Yale University Printing, 2018, ISBN 978-0-300-21000-2, 459 pp.; and David C. Hendrickson, Commonwealth in Peril: American Empire and the Liberal Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0190660383, 287 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. 2 (Feb 7, 2019), pp. 8-10. (p. x.)

- ^ Jan Bloch, Future war and its economical consequences, 1898.

- ^ Joshua Busby, "Warming Globe: Why Climate change Matters More Annihilation Else", Strange Affairs, vol. 97, no. 4 (July / August 2018), p. 54.

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Special Report on Global Warming of 1.v °C, 8 October 2018.

- ^ Sheldon Novick, The Careless Atom, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1969, passim

- ^ Thomas Powers, "The Nuclear Worrier" (review of Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, New York, Bloomsbury, 2017, ISBN 9781608196708, 420 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXV, no. one (xviii January 2018), pp. 13–15.

- ^ Eric Schlosser, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, Penguin Press, 2013, ISBN 1594202273. The volume became the footing for a 2-hr 2017 PBS American Experience episode, too titled "Command and Command".

- ^ Laura Grego and David Wright, "Broken Shield: Missiles designed to destroy incoming nuclear warheads fail ofttimes in tests and could increase global risk of mass devastation", Scientific American, vol. 320, no. no. 6 (June 2019), pp. 62–67.

- ^ Jessica T. Mathews, "The New Nuclear Threat", The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVII, no. 13 (20 August 2020), pp. 19–21. (Quotation from p. 20.)

- ^ Elizabeth Kolbert, "This Close; The solar day the Cuban missile crisis nigh went nuclear" (a review of Martin J. Sherwin's Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crunch, New York, Knopf), The New Yorker, 12 October 2020, pp. 70–73.

- ^ Elizabeth Kolbert, "This Shut; The day the Cuban missile crunch almost went nuclear" (a review of Martin J. Sherwin's Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis, New York, Knopf), The New Yorker, 12 Oct 2020, p. 72.

- ^ Fintan O'Toole, "A Moral Witness" (review of Janet Somerville, ed., Yours, for Probably Always: Martha Gellhorn'southward Letters of Love and State of war, 1930–1949, Firefly, 528 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVII, no. 15 (viii October 2020), pp. 29–31. (Quotation, p. 31.)

- ^ Casey Cep, "Demon-driven: The bigoted views and vivid fiction of William Faulkner", The New Yorker, 30 November 2020, pp. 87–91. (Quotation: p. 90.)

- ^ Sam Tanenhaus, "The Electroshock Novelist: The Alluring Bad Boy of Literary England Has Always Been Fascinated by Britain's Dustbin Empire. Now Martin Amis Takes On American Backlog," Newsweek, July 2 & 9, 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. ix (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27.

- ^ Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. 9 (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27. (Quotation, p. 25.)

- ^ Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. nine (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27. (P. 25.)

- ^ Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Nowadays, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. 9 (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27. (Quotation, p. 25.).

- ^ Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. ix (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27. (P. 26–27.)

- ^ * Ferdinand Mount, "Ruthless and Truthless" (review of Peter Oborne, The Assail on Truth: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and the Emergence of a New Moral Barbarism, Simon and Schuster, February 2021, ISBN 978 i 3985 0100 iii, 192 pp.; and Colin Kidd and Jacqueline Rose, eds., Political Advice: Past, Nowadays and Hereafter, I.B. Tauris, February 2021, ISBN 978 1 83860 004 iv, 240 pp.), London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 9 (6 May 2021), pp. 3, 5–8.

Bibliography [edit]

- Casey Cep, "Demon-driven: The bigoted views and bright fiction of William Faulkner", The New Yorker, 30 Nov 2020, pp. 87–91.

- Carlo Cercignani, affiliate 2: "Physics before Boltzmann", in Ludwig Boltzmann: The Human being Who Trusted Atoms, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-850154-4.

- David Christian, Maps of Time: an Introduction to Large History, University of California Printing, 2005.

- Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Homo Societies, new ed., W.W. Norton, 2005.

- Ariel Dorfman, "A Taxonomy of Tyrants" (review of Ruth Ben-Ghiat, Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present, Norton, 2020, 358 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. ix (27 May 2021), pp. 25–27.

- The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), in Marx Engels Selected Works, volume I.

- Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The Westward and the Balance, Penguin Press, 2011.

- Niall Ferguson, "America'southward 'Oh Sh*t!' Moment," Newsweek, November 7 & 14, 2011, pp. 36–39.

- David Hackett Fischer, The Corking Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History, Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Joshua S Goldstein, Long Cycles: Prosperity and War in the Modern Age, 1988.

- Gordon Graham, "Recurrence," The Shape of the Past, Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-xix-289255-Ten.

- Marshall Yard.S. Hodgson, Rethinking World History: Essays on Europe, Islam, and Earth History, Cambridge University Printing, 1993.

- Walter Kaufmann, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, 1959.

- Arthur Keith, A New Theory of Human Development, Watts, 1948.

- Paul Kennedy, The Ascent and Autumn of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Armed forces Conflict from 1500 to 2000, Random Business firm, 1987, ISBN 0-394-54674-ane.

- Ibn Khaldun, Muqadimmah, 1377.

- Elizabeth Kolbert, "This Close; The day the Cuban missile crunch virtually went nuclear" (a review of Martin J. Sherwin's Gambling with Armageddon: Nuclear Roulette from Hiroshima to the Cuban Missile Crisis, New York, Knopf, 2020), The New Yorker, 12 October 2020, pp. 70–73.

- Andrey Korotayev, Arteny Malkov, Daria Khaltourina, Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Secular Cycles and Millennial Trends., Moscow, 2006, ISBN v-484-00559-0. See especially chapter 2.

- David Lamb and S.M. Easton, Multiple Discovery: The Pattern of Scientific Progress, Amersham, Avebury Press, 1984.

- Pierre-Simon Laplace, A Philosophical Essay, New York, 1902.

- Jackson Lears, "Imperial Exceptionalism" (review of Victor Bulmer-Thomas, Empire in Retreat: The By, Nowadays, and Future of the United States, Yale University Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-300-21000-two, 459 pp.; and David C. Hendrickson, Republic in Peril: American Empire and the Liberal Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0190660383, 287 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. ii (February vii, 2019), pp. 8-x. Bulmer-Thomas writes: "Imperial retreat is not the same as national refuse, as many other countries can attest. Indeed, imperial retreat can strengthen the nation-country just as imperial expansion tin can weaken information technology." (NYRB, cited on p. ten.)

- Robert K. Merton, The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations, Academy of Chicago Press, 1973.

- Ferdinand Mount, "Ruthless and Truthless" (review of Peter Oborne, The Assault on Truth: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and the Emergence of a New Moral Barbarism, Simon and Schuster, February 2021, ISBN 978 ane 3985 0100 3, 192 pp.; and Colin Kidd and Jacqueline Rose, eds., Political Advice: Past, Present and Future, I.B. Tauris, Feb 2021, ISBN 978 1 83860 004 four, 240 pp.), London Review of Books, vol. 43, no. 9 (6 May 2021), pp. 3, 5–8.

- Fintan O'Toole, "A Moral Witness" (review of Janet Somerville, ed., Yours, for Probably Always: Martha Gellhorn'due south Letters of Dear and State of war, 1930–1949, Firefly, 528 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVII, no. 15 (8 October 2020), pp. 29–31.

- Elizabeth Perry, Challenging the Mandate of Heaven: Social Protest and State Ability in China, Sharpe, 2002, ISBN 0-7656-0444-two.

- Malise Ruthven, "The Otherworldliness of Ibn Khaldun" (review of Robert Irwin, Ibn Khaldun: An Intellectual Biography, Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 9780691174662, 243 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVI, no. two (Feb 7, 2019), pp. 23–24, 26.

- George Santayana, The Life of Reason, vol. 1: Reason in Common Sense, 1905.

- Pitirim Aleksandrovich Sorokin, Social and Cultural Dynamics: a Study of Change in Major Systems of Art, Truth, Ethics, Law, and Social Relationships, Boston, Porter Sargent Publishing, 1957, reprinted 1985 by Transaction Publishers.

- Fred Spier, The Structure of Big History: from the Big Bang until Today, Amsterdam University Press, 1996.

- Sam Tanenhaus, "The Electroshock Novelist: The Alluring Bad Boy of Literary England Has Always Been Fascinated by Britain's Dustbin Empire. Now Martin Amis Takes On American Backlog," Newsweek, July 2 & nine, 2012, pp. l–53.

- Arnold J. Toynbee, A Report of History, 12 volumes, Oxford Academy Press, 1934–61.

- Arnold J. Toynbee, "Does History Echo Itself?" Civilization on Trial, New York, Oxford University Press, 1948.

- Thou.West. Trompf, The Idea of Historical Recurrence in Western Thought, from Antiquity to the Reformation, Berkeley, Academy of California Press, 1979, ISBN 0-520-03479-i.

- Marker Twain, The Jumping Frog: In English, Then in French, and And then Clawed Back into a Civilized Language Again by Patient, Unremunerated Toil, illustrated past F. Strothman, New York and London, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, MCMIII. [1]

- Paul Wilson, "Adam Michnik: A Hero of Our Time," The New York Review of Books, vol. LXII, no. 6 (April 2, 2015), pp. 73–75.

- Harriet Zuckerman, Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States, Gratis Press, 1979.

Further reading [edit]

- Bolesław Prus, "Mold of the Earth", an 1884 microstory about the history of the world, reflecting the ebb and flow of homo communities and empires.

External links [edit]

![]() Quotations related to Celebrated recurrence at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Celebrated recurrence at Wikiquote

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historic_recurrence